Advocating for racialized communities, worker rights, the homeless

Pandemics are like guided missiles. They target the most vulnerable. The effects of COVID-19 on three groups—racialized communities, essential workers and people who experience homelessness—are all textbook examples. We have seen the disproportionate impacts throughout. My hope is that in the time between this public health crisis and the next one, we will address the inequities that create such results so that way, the communities we serve will not have to suffer the same way. Before we get there, we must get better at protecting groups who experience these kinds of structural vulnerabilities. But to do that, we must first understand why these groups are vulnerable in the first place.

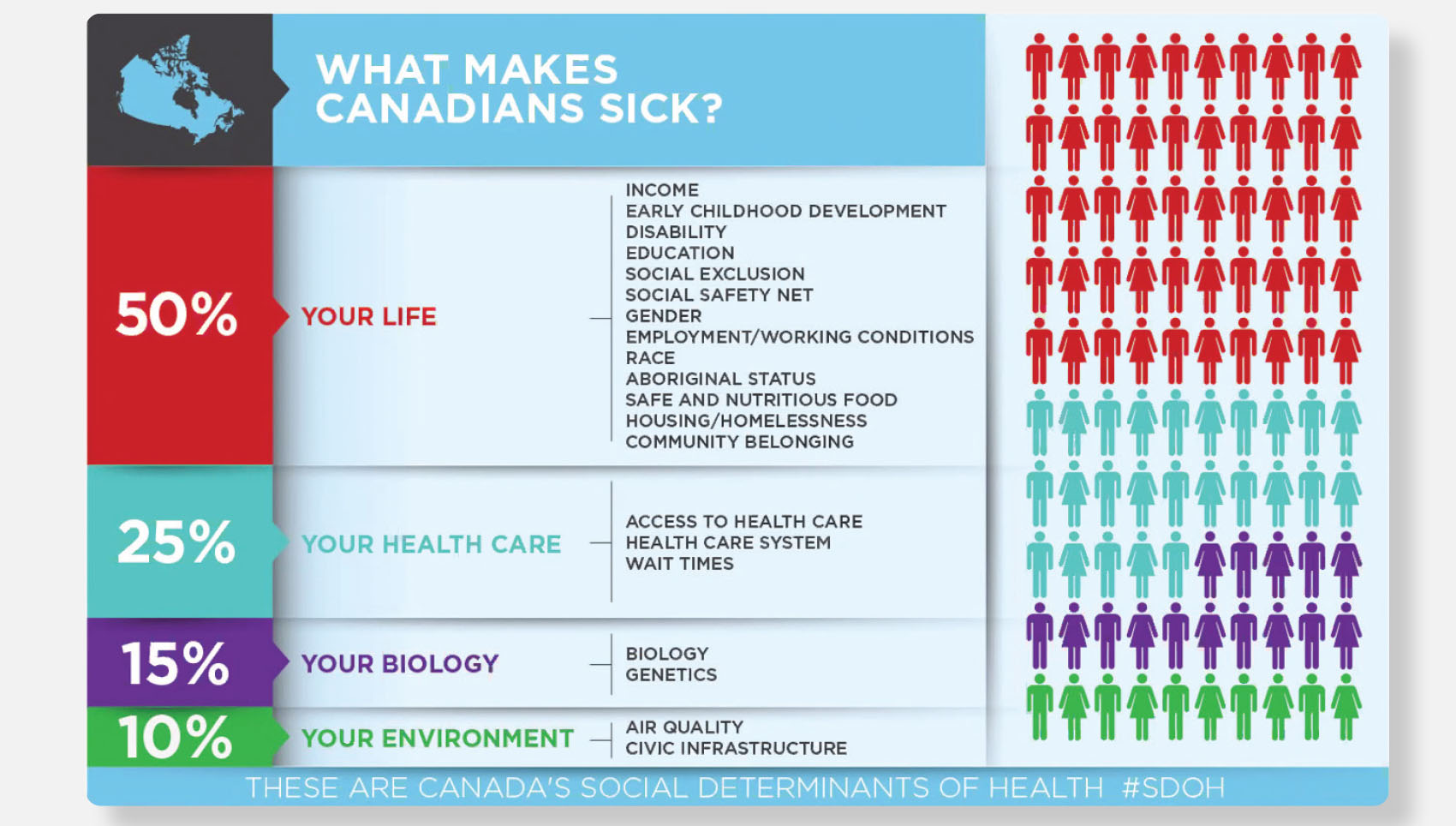

What has made so many Canadians sick since the early days of 2020? The short answer is the virus. Yet, that is not the whole story. So much of this comes down to the same answer as always. For many illnesses, your biology and genetics certainly play a part. So does your access to care. But we also know that over 60 per cent of what makes us sick is social: your income, education, employment, gender, race, housing, the social safety net, food security, a sense of community belonging, early childhood development, ability or disability and more. These are the social determinants of health. We may understand what defines them. What we lack is a conversation about what drives them.

Inequities in the social determinants of health lead to poorer health outcomes including poor mental health, shortened life expectancy, obstetrical complications and cardiovascular disease. But what causes these inequities? That requires a root-cause analysis. The answer is things like racism, sexism, transphobia, xenophobia, classism, colonialism, ableism, capitalism and imperialism.

We have seen how that has played out during the pandemic. For instance, in Toronto, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities comprise 52 per cent of the population but accounted for 83 per cent of the COVID-19 cases in the first wave. Black people make up nine per cent of the city’s population but 21 per cent of cases. That did not get better over time. In the fall of 2020, we still saw 79 per cent of reported cases in Toronto, and 71 per cent of people who were hospitalized, come from among those who identify with a racialized group. Those numbers are shocking but not surprising. Many members of racialized communities face routine disadvantages, and our institutions often perpetuate them at a systemic level.

Yes, racism exists in Canada. It has a long history. It should not be disputed that systemic anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism has led to more disease and lower life expectancies for these groups. COVID-19 is just another in a long line of examples. There is a familiar discourse around groups that have been hard-hit by COVID-19. You’ve heard it. It must be that they are not following the guidelines. That’s why they are at risk. Right? If only they stayed home.

The theme there is blame. Yet consider the higher percentages of people in racialized communities who live in dense housing, or who work in jobs that require them to leave home and operate in close quarters. How are these individuals living? Where do they work? Were they getting infected at work and then bringing the virus home where it spread in their postal code? What structural barriers might have affected their access to education and employment in the past? Or to family wealth accumulation? How many generations back might that go? Keep digging, and that again gets us to a discussion about the root causes of inequities in the social determinants. That is what systemic racism looks like. Race doesn’t determine health-care outcomes. Racism does. This isn’t rhetoric. It has actually impacted lives.

Part of preparing for the next pandemic—and nurturing better outcomes in the interim – is addressing systemic racism. While a complicated concept, as a profession, we must take steps to dismantle the structures of racism, because it is impacting the health outcomes of the people we serve.

Here’s what we can do to start:

We can also be advocates. That is inherent in a physician’s role. It can mean everything from connecting populations at risk with appropriate agencies and supports, to using our voices to call for change, to recognizing one-on-one what our patients need from us.

Vaccine hesitancy is a case in point. We can’t ignore the fact that for many racialized people, hesitancy can stem from mistrust of government and institutions. That includes the health-care system. It is understandable when you look at histories of mistreatment and the trauma that many racialized communities have gone through. If we probe where hesitancy is coming from, we will realize that it is often due to a mistrust of health care. So, it is on us to earn people’s trust and to become trustworthy.

Essential workers are another vulnerable group. At the start of the pandemic, we maybe thought of doctors, nurses and other first responders as essential workers. But so are the people who work in production plants and factories, make our deliveries, drive our buses, serve in stockrooms and checkout lines in grocery stores. And those who clean our facilities. These are essential (and often forgotten) workers too. Their working conditions can be tough, and their benefits few. At one time, one-in-four essential workers in Peel Region were going to work sick with COVID-19. It’s not because they chose to be reckless. It’s because they did not have the option to take time away to be sick for fear of losing their wages or even their job. They did not have paid sick leave.

During the pandemic, many of us have kept ourselves safe by avoiding physical stores and shopping online. Yet workers still have had to process those shipments to keep us supplied. We are not at risk when we click on our phones from our couches. Essential workers in many cases have been. In Brampton, for example, more than 600 Amazon workers at a single warehouse have contracted COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic. Public health eventually shut down the facility. Through all this, Amazon had registered less than five cases at the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board.

Clearly, labour is an important determinant of health. Protecting the health of workers is not just about donning masks or having the right care. It’s also about worker rights, decent wages, a moratorium on evictions, paid sick days. And perhaps it’s about the idea of a basic income, so ultimately, people do not have to choose between their health and paying their bills.

That’s an awful choice, but some people don’t even have that choice. It is far too common for people to lose everything in Canada, including the roof over their heads. And it is killing them. As a palliative care doctor, I see people every day with life-limiting diseases. I would be hard-pressed to name a diagnosis that predictably cuts a person’s lifespan in half at a population level. But one does. It’s a social disease, one that not only affects physical health but someone’s feelings of dignity and self-worth. It’s homelessness.

The pandemic has highlighted the stark connection between homelessness and health. Over 250,000 Canadians experience homelessness each year. For every one person in a shelter, there are 23 others that we do not see who are on the verge of homelessness. In fact, one-in-five Canadian households experience housing vulnerability each year. Compared to the general population, people who experience homelessness are five times as likely to have heart disease and four times as likely to have cancer. The average life expectancy of someone who is homeless is 34 to 47 years. One report out of B.C. showed that in many cases homelessness cuts a person’s lifespan by 50 per cent. Given the strength of this data: Isn’t homelessness itself a life-limiting condition? Shouldn’t it be considered a terminal diagnosis? With an inspiring interdisciplinary team, I treat people experiencing homelessness wherever they are—on the streets, in shelters and under bridges—to help deliver care to them. COVID-19 has devastated these already marginalized citizens.

A study published in January in the Canadian Medical Association Journal found that people with a recent history of homelessness were over 20 times more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19, over 10 times more likely to receive intensive care, and over five times more likely to die within 21 days of a positive test.

Life is tough for people who live on the streets and in shelters and we often don’t make it easier. Think of how we design public spaces, with spikes over grates or protrusions on benches to prevent people from sleeping on them. That’s hostile architecture, it exists in public spaces and in an analogous way, it exists in health care too. Some would say it is a sign of how we treat the homeless in general. By the time of the next crisis, we will hopefully have taken the steps to end homelessness in Canada with the real solution—high quality and affordable housing.

Our health systems are still at the beginning of looking at inequities in the social determinants of health and dismantling the structures that perpetuate them. We need to get rid of the notion of the apolitical doctor who is told, “Stay in your lane.” That idea has percolated for too long in medical culture. For us to inspire change, doctors and our systems must take steps for action, to be political around things like systemic racism, worker rights and homelessness. A lot of community health teams already do incredible work in these areas. That’s a job for all of us. Harm reduction, improved population outcomes and social justice when it comes to health is our lane.

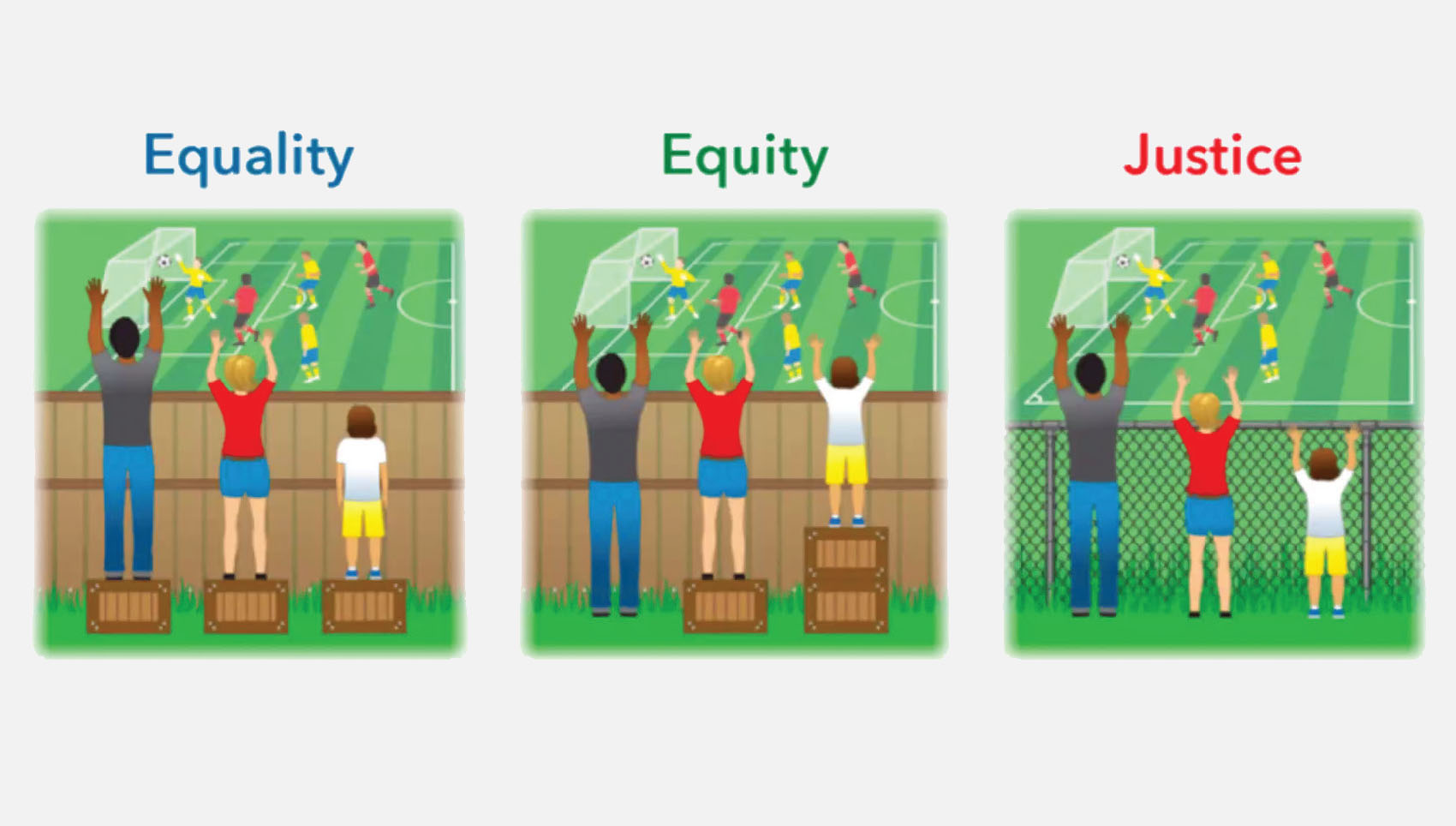

In health care, we are pretty good at equality—giving everyone the same things to be healthy and happy. What we are not as good at is equity—giving people what they truly need, designed for them, to be healthy and happy. We need to move from equality to equity, and ultimately to a justice-based health-care system. One where there are no barriers to health and where we empower people to have the resources they need to make their own healthy lifestyle choices. Our overall well-being and our physical health are intertwined. The pandemic has put that idea in the crosshairs.

There is a saying that during COVID-19 we may have all weathered the same storm, but we were not all in the same boat. Some of us were in yachts, some sailed along with the wind at our backs, and others were in life rafts barely surviving. We must address the root causes now so that health inequities are eliminated. It is a necessary step on the path toward healing.

Dr. Naheed Dosani is founder and lead physician of the Palliative Education and Care for the Homeless (PEACH) Program at the Inner City Health Associates, in Toronto. He is also medical director of the Region of Peel’s COVID-19 Isolation/Housing Program and serves as a lecturer in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto.