This article originally appeared in the May/June 2020 issue of the Ontario Medical Review magazine.

The steady, matter-of-fact voice is carried across Canada as Dr. Stephen Oldridge tells CBC Radio’s Brent Bambury on April 3: “I’m not an expert. I’m just a family doctor in a small town.” However, Canadians want to hear what this doctor has to tell them. They already know the name of the nursing home where he cares for residents — Pinecrest in Bobcaygeon. At the time of the interview, in the 65-bed facility, 20 patients have died. Half the residents were showing symptoms. One-third of staff had been diagnosed. The physician tells listeners that in his 30 years of practice, he’s “never seen anything like this.”

Unfortunately, the situation in Pinecrest was seen in many other long-term care homes. Pinecrest’s outbreak was heavily publicized because it was among the earliest. However, it turned out to be more of a harbinger than an outlier. By late April, 79 per cent of all COVID-19 related deaths in Canada were connected to long-term care and seniors’ homes. A couple of weeks earlier, in announcing an action plan, Ontario Premier Doug Ford summed up the situation. “The sad truth is our long-term care homes are quickly turning into the frontline of the fight against this virus,” he said.

Dr. Oldridge described for listeners the grim reality of geriatric care when COVID-19 spreads to the frail elderly: “There is no treatment, I’m afraid, there are only supportive measures available — supporting symptoms as they arrive. It is palliative care.”

After watching the COVID-19 crisis overwhelm hospital intensive care units (ICUs) in other countries, it was understandable that Ontario, like other places in North America, was focused on the potential crisis in hospitals. The pandemic lockdown and physical distancing that was communicated to the public highlighted the importance of preventing a surge in cases arriving in ICUs.

But a viral outbreak does not necessarily follow a predictable pattern based on the experience of other places. It hits a population where it’s vulnerable. The frail and elderly care in long-term care settings, a sector that was already resource-challenged prior to the pandemic, became Ontario’s most pressing and grim front in the war against COVID-19. So, when a surge arrived in long-term care another shortage developed — expertise in palliative care.

In dealing with the COVID-19 crisis, primary care physicians and those in smaller communities were feeling somewhat isolated as they led the fight in long-term care and other community settings.

“Some of the key things we’ve been hearing is that frontline clinicians are asking for guidance around end-of-life care and symptom management. These clinicians need brief, concise guides on how to have goals-of-care conversations and generally manage end-of-life care,” says Dr. Robert Sauls, provincial and clinical co-lead of the Ontario Palliative Care Network.

This demand for palliative care support and guidance led the OMA to convene webinars on palliative care specific to the COVID-19 pandemic. The sessions were tailored to specialists and family physicians and explored challenges and solutions in palliative care and end-of-life conversations from the urban, suburban, rural and palliative perspective (for more information, see OMA Resources for Physicians below.)

Dr. Pamela Liao, Chair, OMA Section on Palliative Medicine, opened the meetings. “We’re all feeling the pressure in managing COVID patients. I find it so different from all the things I’ve been taught about being able to show empathy, holding hands and making eye contact,” said Dr. Liao. “We’re in a totally different world where families are grieving and saying goodbye to a loved one while separated.”

All OMA COVID-19 resources and information for physicians is continually updated, and can be accessed via a dedicated web page. Below is an overview of OMA resources that may be of interest to members in relation to the article, “COVID-19 brings increased deaths to new settings: putting palliative care expertise within easy reach of every physician.”

The OMA has compiled a COVID-19: End-of-Life Planning and Care Toolkit that highlights resources shared by experts in end-of-life care and key provincial stakeholders. This toolkit aims to equip physicians with the knowledge, resources and skills to provide primary level palliative care for patients and their families during the COVID-19 crisis.

Palliative care and COVID-19 pandemic planning: Dr. Robert Sauls, Co-Chair, Provincial Clinical Co-Lead, Ontario Palliative Care Network, and Dr. Meera Dalal-Burns, a palliative care specialist and internist at St. Michael’s Hospital, hosted a webinar in early April on Palliative Care and COVID-19 Pandemic Planning. The webinar and question-and-answer session was moderated by Dr. Pamela Liao, Chair, OMA Section on Palliative Medicine. Listen to the palliative care and pandemic planning recording.

Palliative care and COVID-19 forum: Approach to goals of care conversations: In conjunction with Hospice Palliative Care Ontario, Dr. Pamela Liao, Chair of OMA Section on Palliative Medicine, and facilitators Dr. Nadia Incardone, Dr. Jeff Myers, Dr. Leah Steinberg, and Dr. Jennifer Arvanitis, host an interactive webinar and Q&A to provide guidance to physicians on having conversations with COVID-19 patients around goals of care. Listen to the approach to goals of care conversations recording.

The OMA is aware of growing concerns over potential critical care and palliative care drug shortages in the province. We are in regular contact with the Ministry and the Pharmacy Association and will provide further updates as soon as more information is available. It should be noted that the government has made changes to the access and dispensing of certain drugs and assistive devices to alleviate pressures on the system).

The OMA has provided information and resources related to controlled drug shortages and medical treatments.

Dr. Meera Dalal-Burns is a palliative care physician at St. Michael’s Hospital. Her work in providing consultations within her institution was disrupted by infection control at a time when demand for palliative consults was increasing. That meant shifting some of her work toward finding new ways of supporting physicians in other specialties with palliative care expertise.

“Experienced physicians might be used to having end-of-life conversations, and have a personal style that works well, but were not used to resource-limited conversations or virtual conversations, and we don’t have a lot of time to develop a style now,” says Dr. Dalal-Burns.

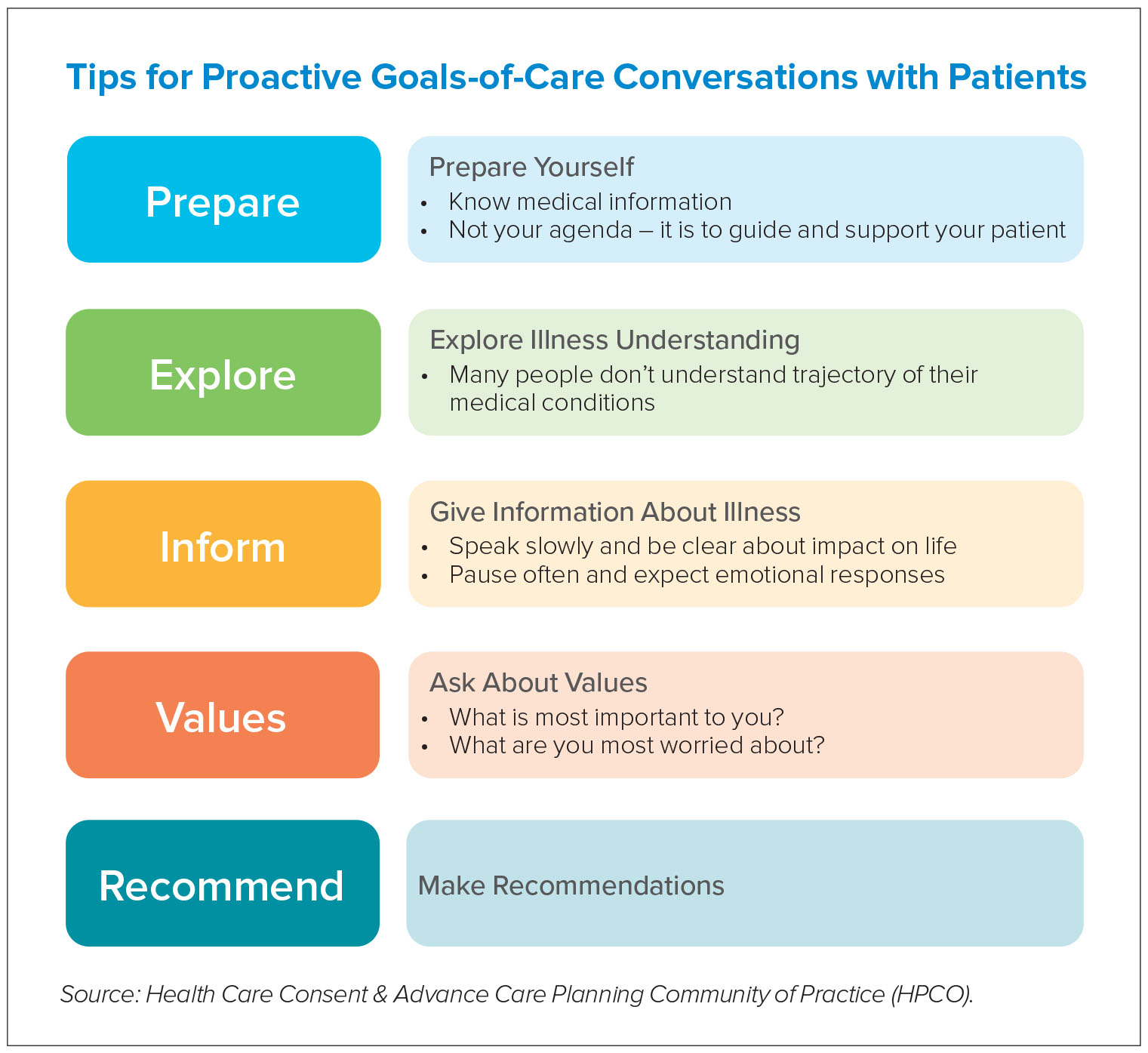

This shift can, of course, extend beyond the walls of an institution. Dr. Dalal-Burns points to various conversation guides for end-of-life and goals-of-care that have been adapted for COVID-19 and can be used by physicians across Ontario in various settings. “We’re seeing a general interest and willingness in having everyone step up in being part of end-of-life care and growing consciousness around these issues,” she says. “When we talk to our emergency medicine and outpatient colleagues, they expressed a desire to have these conversations but felt they did not have the luxury of being able to sit with someone for a long time,” she says. “We need an approach that is practical, fits the demands of their time, can be done both in person and virtually and is also meaningful. This is where a conversation guide can help.”

Conversation guides are available, including guides that can be displayed on a smartphone, which can be especially helpful in having remote conversations with patients and families.

Dr. Dalal-Burns’ own advice to physicians is to keep such conversations focused. “In this crisis, we don’t have the luxury of being able to sit with someone and hold their hand,” she says. “The shorter the questions, the fewer the questions and the more open-ended, the more meaningful and focused that conversation will be.”

It’s been well documented that patients who have serious illness are at increased risk from COVID-19. This creates an opportunity for all clinicians, including family physicians, to introduce the topic of advance care planning to patients.

Dr. Leah Steinberg, a family physician in Mount Sinai Hospital’s division of palliative care, encourages primary care physicians and specialists to reach out to vulnerable patients. “While advance care planning conversations have always been important, COVID-19 is giving a specific focus and need for these conversations.” While acknowledging that many clinicians worry about upsetting or frightening their patients, Dr. Steinberg believes most patients see the benefit in the current COVID-19 context. “With all of the public health information that is out there, patients are pleased to be getting information specific to them from their clinician,” says Dr. Steinberg.

Proactive conversations are important for two reasons: First, clinicians can confirm the patient’s substitute decision-maker. Second, they can identify a patient’s values and goals. This might include determining where the patient wants to be cared for should they become seriously ill. Some may prefer to be cared for at home, especially if visitors are not allowed in hospital. Dr. Steinberg highlights the e-learning modules and conversation guides on SpeakUpOntario as useful resources.

“When asking my patients about their values and goals, my two favourite questions are: given the information you now know about this illness, what would be most important to you? As you think about the future, what are you most worried about?” says Dr. Steinberg. “Those questions generally get the conversation to what people’s goals are, then you can summarize and make some suggestions.”

In the fight against COVID-19, medical supply shortages have been a concern, including a race to acquire personal protective equipment and ventilators. Health officials will also need to keep an eye on supply of medicines and equipment used in palliative care.

The OMA’s Past President Dr. Sohail Gandhi, a family medicine practitioner in Stayner and a medical director of a long-term care home, advises other physicians to maintain a “COVID stock box” of medications that will be needed. “Many of the medicines used in palliative care are not widely used by other specialties, although opioids are used in many settings. Maintain a supply within the long-term care home of the medicines you know you will need, without getting into hoarding,” says Dr. Gandhi.

Beyond this practical measure, the OMA is advocating that doctors be included in the provincial conversation around medicine supply, including transparent monitoring with a regional breakdown. “We need to have a handle on where shortages are occurring, other than word of mouth, including palliative care equipment. Shortages in the home care sector will mean more people coming to hospitals for end-of-life care. There needs to be planning at the national, provincial and regional level,” says Dr. Gandhi.

While the OMA has an entire section on its website dedicated to COVID-19, including on palliative care, they are encouraging the provincial government to lead development of provincially co-ordinated work on guidelines, including symptom management and general care. With palliative care increasingly conducted via remote connections by doctors in a variety of specialties, billing codes for such a service also need to be clearly understood and accessible.

Physicians have also had questions about certifying death and capturing the impact of COVID-19. The provincial government has recently announced that all long-term care deaths in Ontario will be managed by the Office of the Chief Coroner when it comes to providing the death certificate.

In an April 16 OMA webinar, Dr. Jennifer Arvanitis, a family physician with the Temmy Latner Centre for Palliative Care, shared advice with physicians in other settings regarding listing COVID-19 on death certificates.

Certificates list the sequence of events that led to the death in reverse chronological order, such as “acute respiratory distress syndrome, secondary to pneumonia, secondary to COVID-19.” The relative contributing factors are listed in Part II, such as diabetes or hypertension — health conditions that made the person more susceptible to death but did not cause death. If the patient was infected with COVID-19, but cause of death was another illness, “COVID-19” should be listed in Part II. If it was likely the patient had COVID-19 but died before a positive test could be returned, this should also be captured as “probable.”

“Given the evolving understanding of how COVID-19 impacts health, COVID infections should always be listed in the death certificate,” says Dr. Arvanitis. “Like other things in medicine, we use a balance of probabilities. We don’t have to be 100 per cent correct all the time in terms of cause of death. If a patient had COVID-19 symptoms and clearly had exposure, it is reasonable to put ‘possible COVID-19’ even if you’re never going to have confirmation.”

As it becomes clear that risk from COVID-19 may be in Ontario communities for months and possibly years, physicians will be discussing implications for vulnerable patients, and their wishes should they become seriously ill. In mobilizing collective action to protect life in a pandemic, the response to COVID-19 is often characterized as a war. Those caring for the frail and elderly may have been the shock troops who faced the first tragic but noble battle. As Dr. Gandhi observed: “This is an unprecedented crisis we’re dealing with, and the work OMA members are doing in palliative care is going to be, unfortunately, much needed over the next while. I’m grateful for all those colleagues who I know will provide compassionate care to patients and families.”

David McLaughlin is a Toronto-based writer.