Prescription for Ontario

Doctors’ Solutions for Immediate Action

In spring 2023, we identified three urgent health-system crises related to primary care, administrative burden and capacity in community-based care. Now, we call on the province to heed our warnings. Investing in our solutions will yield the greatest results for our health-care system.

Learn about the solutionsDoctors aim to make the system better for all of us

Prescription for Ontario: Doctors’ 5-Point Plan for Better Health Care, released in October 2021, outlines the actions necessary to fix the province’s health-care system. It provides 87 recommendations to address new and long-standing issues in the overall system, including 12 that speak to the unique barriers to adequate health care in northern Ontario.

The Prescription for Ontario was informed by the largest consultation in its 140-year history. More than 1,600 physicians and physician leaders provided their expert advice. More than 110 health-care stakeholders, social service agencies and community leaders offered solutions from their unique perspectives. Almost 8,000 Ontarians, representing 600 communities, shared their health-care priorities through an online survey.

A second round of consultations with members and stakeholders resulted in the OMA's development of a progress report in May 2023 designed to measure the successes and failures to date in implementing the original recommendations and help guide its advocacy efforts going forward.

Since then, the OMA consulted broadly and brought together the collective expertise of physicians and other key stakeholders to find tangible and immediate solutions to fix these crises.

Get the full report

We need a more collective way of thinking about health care, one that focuses on solutions, strengthens the alignment between patient priorities and system capacity, and directs provincial financial and human resources towards the best possible health outcomes.

Download Prescription for OntarioHave your say

Share your comments on the OMA's Prescription for Ontario

Reduce wait times and the backlog of services

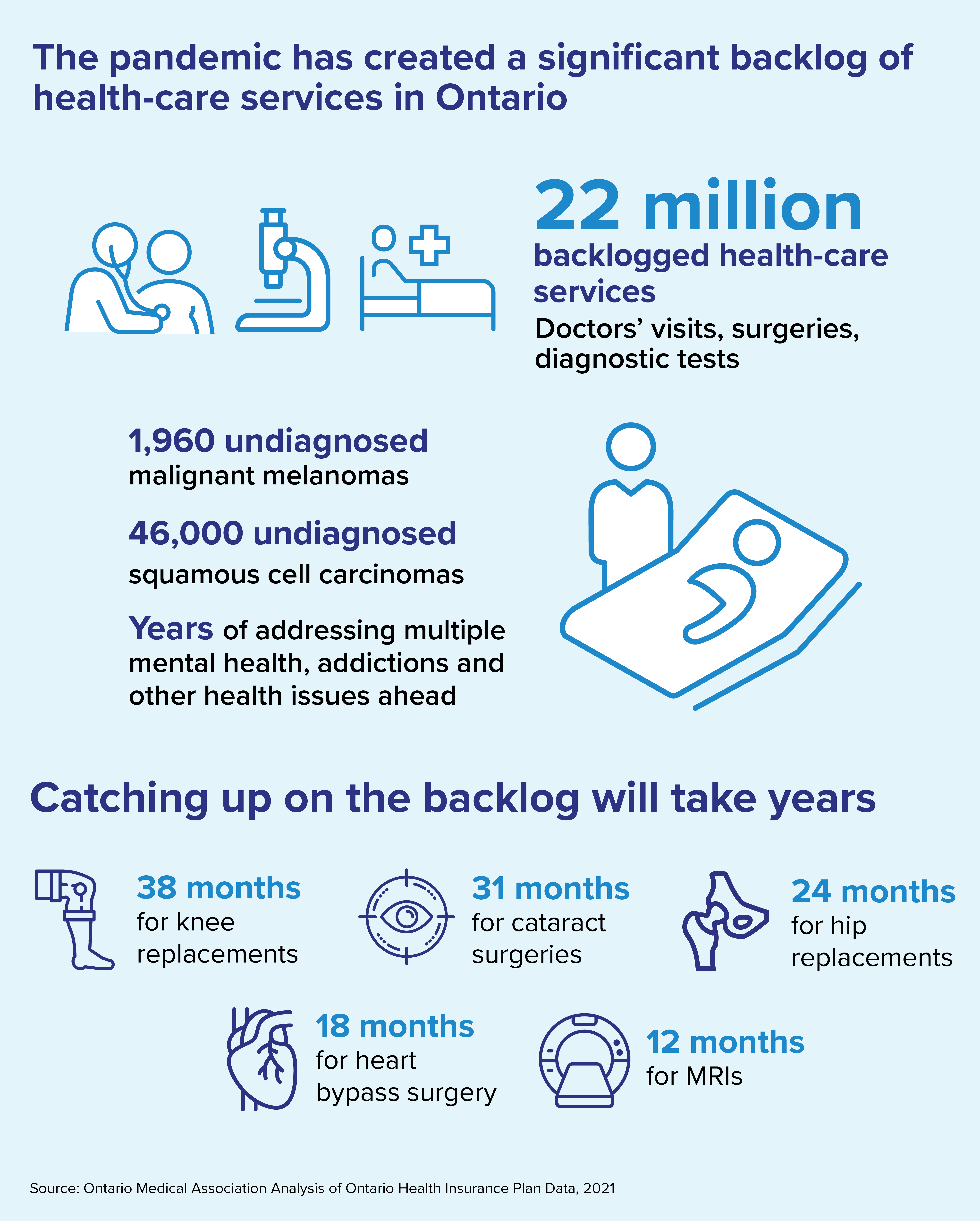

Sick patients don’t have time to wait, but the COVID-19 pandemic has created a backlog of almost 22 million medical services — more than one patient service for every Ontarian, from the youngest to the oldest.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a backlog of almost 22 million medical services — more than one patient service for every Ontarian, from the youngest to the oldest.

These delayed services include preventive care, cancer screening, surgeries and procedures, routine immunizations and diagnostic tests such as MRIs and CT scans, mammograms and colonoscopies. Doctors are seeing patients sicker than they ought to be because of serious conditions left undetected or untreated during the pandemic.

Sick patients don’t have time to wait. However, focusing on the pandemic backlog alone ignores the bigger problem. We can’t solve Ontario’s long-term problem of wait times and hallway medicine if the health-care system remains inefficient and disconnected.

Ontarians agree. Other than the pandemic, wait times is the issue most frequently selected — by 29 per cent of respondents — as the top priority for health care in the OMA’s online public survey.

Additionally, 21 per cent of Ontarians who responded to the survey selected “Wait times at our hospitals are too long and need to be reduced” as the statement that best represents their view on health-care delivery in their community.

A new model of care

Integrated Ambulatory Centres: A Three-Stage Approach to Addressing Ontario’s Critical Surgical and Procedural Wait Times calls for immediate attention to eliminate the pandemic backlog of health-care services and the creation of a new model of care called Integrated Ambulatory Centres.

Read the executive summary.

Read the full proposal.

Recommendations to reduce backlog and shorten wait times

- Provide adequate funding to address the backlog of services in hospitals and community clinics

- Evolve the model of surgical care delivery to include a greater portion of services delivered in community-based specialty settings outside of hospitals

- Ensure enough nurses and technologists to expand MRI and CT machine hours, and for ultrasound and mammography

- Greater efforts to educate young people about healthy lifestyles and disease prevention, including an adequately funded tobacco strategy, which will lead to better long-term health and reduce future stress on the system

- Expand the use of home remote monitoring programs to streamline pre- and post-surgical delivery

- Ensure sufficient health human resources to meet Ontario’s needs

- Enhance data collection and timely data sharing to support planning, measurement and evaluation

- Better integration of health-care service provision with public health and other services, including but not limited to palliative care, long-term care, home care and community care

“Cancer isn’t waiting for the pandemic to be over.” — Dr. Timothy Asmis, chair, OMA Section on Hematology and Medical Oncology, Ottawa

Fixing doctor shortages

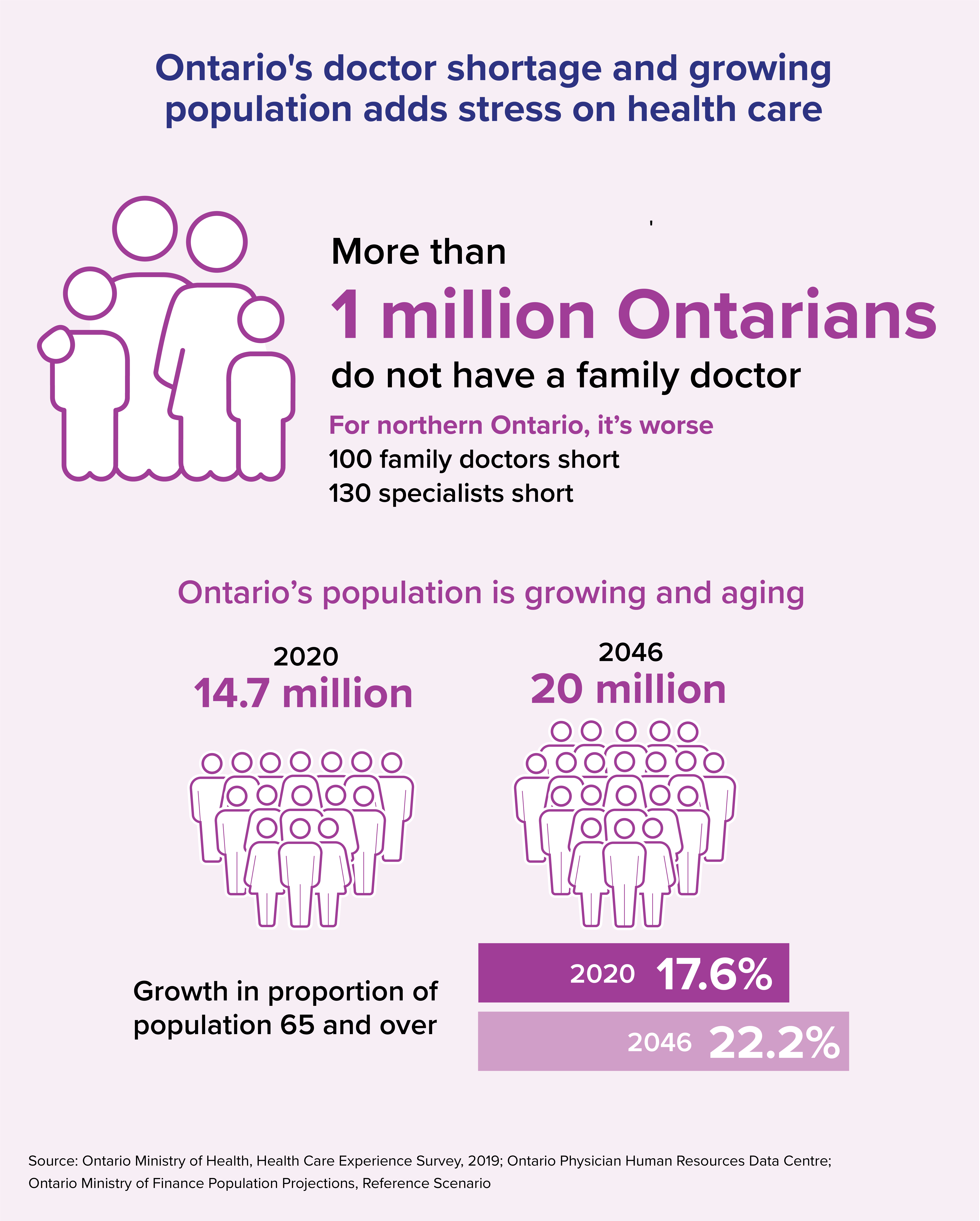

Ontario continues to experience doctor shortages in many regions — especially in the north and remote and rural communities — and in certain specialties such as family medicine, emergency medicine and anesthesia. This is being felt by Ontarians.

Twenty-six per cent of respondents to the OMA’s online public survey chose “We don’t have enough doctors” as the statement that best represents their view on health-care delivery in their community.

Ontario’s doctors know that prevention is key to long-term health and positive outcomes. The public also recognizes this, with 32 per cent of survey respondents choosing “We need to do more to keep people healthy and out of hospitals and doctors’ offices” as the statement that best represents their view on health care delivery in their community. Respondents in Toronto and the Greater Toronto Area particularly hold this view

Primary care is the foundation of Ontario’s health-care system. But at least one million Ontarians don’t have a family doctor. Family doctors help patients stay healthy, prevent disease by identifying risk factors, manage chronic disease and get their patients access to specialists and other health-care services when needed.

Without access to doctors, many patients needlessly worry and suffer. We need robust data about our physician workforce and we need to use that data wisely to plan for our future population needs. We also need to support doctors so that all patients can get equitable and timely access to the care they need.

Recommendations to address unequal supply and distribution of doctors

- Create a detailed analysis, based on high-quality data, that accounts for the types and distribution of doctors to meet population needs

- Establish a set of best practices around physician supports to help ensure Ontario has the right doctors in the right places at the right times

- Use best evidence regarding forecasted population need, increasing the number of medical student and residency positions

- Support students from remote, rural and racialized communities to go to medical school aligned with populations in need

- “Let doctors be doctors” whereby they spend more time with patients doing the things that only doctors can do and less time on paperwork or other tasks

- Help doctors trained in other jurisdictions become qualified to practise here

- Invest in more training and educational supports for practising doctors

Expand mental health and addiction services in the community

In any given year before the pandemic, one in five people in Canada experienced a mental health problem or illness. Doctors continue to provide excellent care, but they do not have enough hours in a day to accommodate the tsunami of new patients.

In any given year, one in five people in Canada experiences a mental health problem or illness. But that was before the pandemic:

- A survey by the Conference Board of Canada and the Mental Health Commission of Canada found that 84 per cent of respondents reported their mental health concerns worsening since the start of the pandemic, with their major concerns being family wellbeing, their future, isolation/loneliness and anxiousness/fear.

- More than one-third of those with a COVID-19 diagnosis may develop a lasting neurological or mental health condition.

- A study by Deloitte using modelling from past disasters suggests Canada will see “a two-fold increase in visits to mental health professionals and possibly a 20 per cent increase in prescriptions for antidepressants relative to pre-COVID-19 levels.”

“A frantic mother brought her teen daughter to Emergency on a busy Saturday. In a desperate cry for help, the girl had cut herself and needed stitches. Mom and daughter waited six long hours to see me. It was clear the girl’s mental health needs far outweighed her repairable wound. But all I could offer them was a piece of paper with a referral phone number to call on Monday. It was obvious, our health-care system was failing her. I felt helpless.” — Dr. Rose Zacharias, emergency medicine physician and outgoing OMA president, Orillia

Psychiatrists, primary care doctors, pediatricians and addiction medicine specialists continue to provide excellent care for these patients. But they do not have enough hours in the day to accommodate the tsunami of new patients asking for help. There must be greater accessibility to affordable and publicly funded services in the community so everyone can get the treatment they need.

Doctors and other front-line health-care professionals were experiencing high levels of burnout before the COVID pandemic. According to surveys conducted by the OMA’s Burnout Task Force, just prior to the pandemic in March 2020, 29 per cent of Ontario doctors had high levels of burnout with two-thirds experiencing some level of burnout. By March 2021, these rates had increased, with 34.6 per cent reporting high levels of burnout and almost three-quarters reporting some level of burnout.

Burnout is primarily caused by issues in the health-care system, so system-level solutions are needed to address it. And if doctors, nurses and others providing care burn out, this impedes access to care for patients.

“Only one in five young people who need mental health services receives them.” — Dr. Sharon Burey, behavioural pediatrician and president of the Pediatricians Alliance of Ontario

Recommendations to improve access to mental health and addiction care

- Province-wide standards for equitable, connected, timely and high-quality mental health and addiction services to improve the consistency of care

- Expand access to mental health and addiction resources in primary care

- Specific mental health supports for front-line health-care providers

- Ensure that appropriate resources are in place to provide virtual mental health services where clinically appropriate

- Increase funding for community-based mental health and addiction teams where psychiatrists, addiction medicine specialists, family doctors, nurses, psychologists, psychotherapists and social workers work together

- More mental health and substance awareness initiatives in schools and in communities

- Make access to care easier by defining pathways to care, navigation and enable smother transitions with the system

- Build service capacity for young patients moving into the adult system

- Reduce the stigma around mental health and addiction through public education

- More resources to fight the opioid crisis, particularly in northern Ontario where the crisis is having a significant impact and resources are limited

- Increase the number of supervised consumption sites

Related stories from the Ontario Medical Review

Fall 2021 issue

Doctors document the devastating fallout on mental health

Fall 2021 issue

Will mental health issues be the pandemic’s legacy?

Improve home care and other community care

In 2019-20, there were 1.3 million hospital bed days used by alternate level of care patients. This creates a major bottleneck that increases surgical wait times, leads to hallway medicine and doesn’t make financial sense.

In 2019-20, there were 1.3 million hospital bed days used by alternate level of care patients. An alternate level of care patient is defined as a patient in hospital who is stable enough to leave but there isn’t a long-term care bed, hospice bed or rehabilitation bed for them to transfer to, or not enough home-care services available for them to return home safely.

When hospital beds are used by patients who don’t need to remain in hospital, this creates a major bottleneck that increases surgical wait times and leads to hallway medicine. And it doesn’t make financial sense.

According to the Ontario Hospital Association, “it costs approximately $500 per day to provide care for a patient in hospital, $150 in long-term care and even less for home and community care. More importantly, hospitals have less room to treat people who really need to be there, or to accommodate a sudden increase in patients during the winter flu season. Unfortunately, this means too many patients receive care in hallways and other unconventional spaces. It is impossible to end hallway medicine without addressing these rising (alternate level of care) rates.”

“Who gets palliative care should not be a postal code lottery.” —Dr. Pamela Liao, family doctor and chair of the OMA Section on Palliative Medicine, Toronto

Home care

Home is where many patients want to be and can be.

High-quality home care provided by a team of doctors, nurses, therapists and personal support workers allows people of all ages to recover from surgery, injury or illness at home. It also reduces the number of emergency department visits and admissions to hospital, helps patients better manage chronic illness, lets seniors live safely and comfortably at home longer, and allows people to be supported if they choose to die at home.

A stronger, more connected and more responsive home-care system would also relieve family members and caregivers, who are too often underequipped and overwhelmed.

- Develop province-wide standards for timely, adequate and high-quality home-care services

- Increase funding for home care and recruiting and retain enough skilled staff to provide this care

- Embed home care and care co-ordinators in primary care so patients have a single access point through their family doctor

- Ensure people without a family doctor can still access home care seamlessly

- Enable electronic sharing of information between doctors, care co-ordinators and home-care providers

- Expand a direct funding model so patients can customize their home care according to need

- Reduce needless administrative paperwork so more time can be spent on actual patient care

- Provide tax relief for families who employ a full-time caregiver for a family member

Strengthen public health and pandemic preparedness

Public health defends the health of the entire community. Not only does it help combat pandemics and other public emergencies, but a strong system led by specially trained doctors preserves health and prevents illness every day.

Public health preserves and defends the health of the entire community. In addition to combatting pandemics and other public health emergencies, a strong public health system led by specially trained public health doctors preserves health and prevents illness every day.

Local public health units track cases of more than 60 communicable diseases; inspect restaurants for health hazards; ensure the safety of private wells in rural areas; promote health in disadvantaged communities; lead routine vaccinations; operate supervised consumption sites; and respond to complaints of retailers selling tobacco or cannabis to children.

We also need to plan and prepare for the next pandemic now. Ontario must have a robust public health system with the resources it needs to protect the entire population’s health, with clearly defined roles across local public health units, Public Health Ontario, Ontario Health and the Ontario Ministry of Health.

Pandemic exposes deep cracks in health care

Anyone who has turned to the health-care system personally or has helped a loved one through an illness knows the expertise and dedication that doctors bring to the table every day. But there are also gaps in our system, things we could improve upon, and the worst public health crisis of our generation has laid these elements bare.

Recommendations to build on the current strengths of our public health system overall

- Enhance local public health to ensure it can be a strong local presence for health promotion and protection

- Provide a clear, adequate and predictable funding formula for local public health units that returns to 75 per cent paid by the province and 25 per cent paid by municipalities

- Ensure Ontario's public health system has highly qualified public health doctors with the appropriate credentials and resources

- Increase the investment in public health information systems so we can better collect, analyze, share and use information in more thorough and timely ways to improve decision-making, and asking the federal government to increase its investment in public health to provide the infrastructure to support standardized data collection and analysis across jurisdictions

- Carry out an independent and unbiased review of Ontario’s response to the pandemic including the public health system — including its strengths and weaknesses during pandemic and non-pandemic times including roles and responsibilities — before considering any changes

- Enhance the ability of Public Health Ontario to carry out its mission/mandate which includes robust public health science and laboratory support, including providing increased funding for hiring of additional public health trained physicians

“To respond to a pandemic of this magnitude in the digital age, it is vital for the Ontario public health system to have access to current, effective and interconnected digital tools and resources to help us manage what we are measuring in real-time. This allows public health professionals to do the work that they are trained to do: investigate, collaborate and mitigate the risk to the public's health.” — Dr. Michael Finkelstein, chair, OMA Section of Public Health Physicians, Toronto

Recommendations to prepare for the next pandemic

- Require by legislation a provincial pandemic plan, including a mandatory review and update every five years to reflect changes in local public health practice, medical science and technology

- Implement a standardized pandemic plan across public health units that is sufficiently flexible to account for differences and inequities across this diverse province

- Sufficiently resource Public Health Ontario to be the central scientific and laboratory resource during a pandemic or public health emergency, including ensuring it has the complement of public health specialist physicians needed to meet its mandate during a public health emergency

- Strategic investments for pandemic planning for public health units so their resources aren’t drained from the other important work they do every day during a crisis

- Ensure adequate funding to recognize additional workloads during pandemics

“To respond to a pandemic, we need interconnected digital tools to help us manage in real time.” — Dr. Michael Finkelstein, chair of OMA Section on Public Health, Toronto

Give every patient a team of health-care providers and link them digitally

Patients are healthier, have fewer hospital admissions and are more satisfied when they have a team of care providers, including not only family doctors and specialists, but also nurses, dietitians, physiotherapists and others.

Team-based and collaborative care

Patients do better when they have a team of care providers, including not only family doctors and specialists but also nurses, dietitians, physiotherapists and others. Where these teams exist, patients have faster and easier access to specific care they need so are healthier, have fewer hospital admissions and are more satisfied. System costs are also reduced.

Most family doctors across Ontario work in different types of practice models that each provide unique benefits to their patients, such as comprehensive care, preventive care and chronic disease management. However, not all practice models allow for the inclusion of other health-care professionals. Most doctors are not able to choose the model of care that is best for their patients and their community.

Recommendations to provide patients with access to family-care model of practice that works best for them

- Increase funding and support for effective team-based and integrated care in all primary care models

- Let family doctors choose the type of practice model that works best for their patients and their community

- Open up the Family Health Organization capitation model of care to all doctors who wish to practice that way

- Increase the number of care co-ordinators to help patients access care more quickly and easily, and have these co-ordinators work directly in primary care settings

- Enable team-based and integrated care settings not only around primary care, but around diseases or specialties

- Optimize the currently legislated Ontario Health Teams, including ensuring physician leadership in the process, as a way to integrate health-care services for the benefit of patients across the province

“Being able to offer virtual psychotherapy during the pandemic has expanded psychiatrists’ ability to better meet the needs of marginalized populations by offering consistent treatment, without some of the barriers that would have previously prevented people from accessing care.” — Dr. Renata Villela, psychiatrist and vice-chair, OMA Section on Psychiatry

Virtual care

Virtual care is another way for patients to receive excellent care from their doctor using a phone or computer to communicate.

Doctors pushed hard at the beginning of the pandemic to enable more access to virtual care for their patients. Without virtual care, the pandemic backlog of almost 20 million delayed patient services would be much greater. Virtual care has literally saved lives and is especially valuable for those who are elderly or ill, those who have trouble getting to the doctor’s office, or those who live in rural and remote communities.

The temporary OHIP codes being used by doctors to provide virtual care during the pandemic expire in September 2022. These virtual care codes must be made permanent and more flexible for doctors to be able to provide their patients with the best care possible.

How we think about the future of virtual care is also important because it works best where it fosters a continuous relationship between a patient and their regular health-care provider. Research shows that patient outcomes are better when there is a trusted and familiar relationship.

Recommendations to ensure all patients continue to benefit from virtual care

- Implement permanent OHIP fee codes for virtual care services provided by phone, video, text and email, ensuring that patients can access virtual care for any insured health-care service that can be appropriately delivered through electronic means

- That the government partner with internet providers so that Ontarians who cannot afford internet services (for example, those living in public or supportive housing, relying on Ontario Works or Ontario Disability Support Program, and seniors receiving the Guaranteed Income Supplement) can get internet services at a greatly reduced rate, to ensure all patients benefit from virtual care

“If specialists could quickly access a patient’s history, this will save time and resources.” — Dr. Mariam Hanna, chair, OMA Section on Allergy and Clinical Immunology

Linking existing digital health records systems

Most people have experienced the frustration of repeating the same information to different health-care providers, or at the hospital or before a test. They’ve likely also been told by their pharmacist that a fax to renew a prescription will be sent to their doctor.

In Ontario, doctors, hospitals, labs and pharmacists use different digital medical records systems, and these systems aren’t all linked. That means nine out of 10 Ontario doctors still must use fax technology to share patient information with other professionals on a patient’s care team.

Connecting these different systems would reduce the administrative burden and free up time better spent on direct patient care. For example, if each of Ontario’s doctors could save one hour a day and see two additional patients, more than 60,000 additional patients would receive care each day, or one million more patients a month.

Recommendations to improve sharing of a patient's medical information among their health-care providers

- Link doctors’ electronic medical records systems, hospital information systems, and lab and pharmacist systems so they can all talk to each other

- Streamline the approval, development and implementation of new digital health technologies, including remote patient monitoring

Recommendations to accelerate innovation in health care

- Better connecting Ontario’s existing innovation, incubator and accelerator investments with physicians and public health-care leaders

- Make health and life sciences one of the priority areas for economic development and research and development government funding programs

- Leverage public and private sector financing, research, development, and health-care expertise to spur the development and use of Ontario made health-care innovations

- Investigate greater use of remote patient management technologies, which can be especially helpful in managing chronic disease

- Prioritize funding for data-sharing tools already in place such as the Clinical viewer and HRM

Improve access to care in northern Ontario

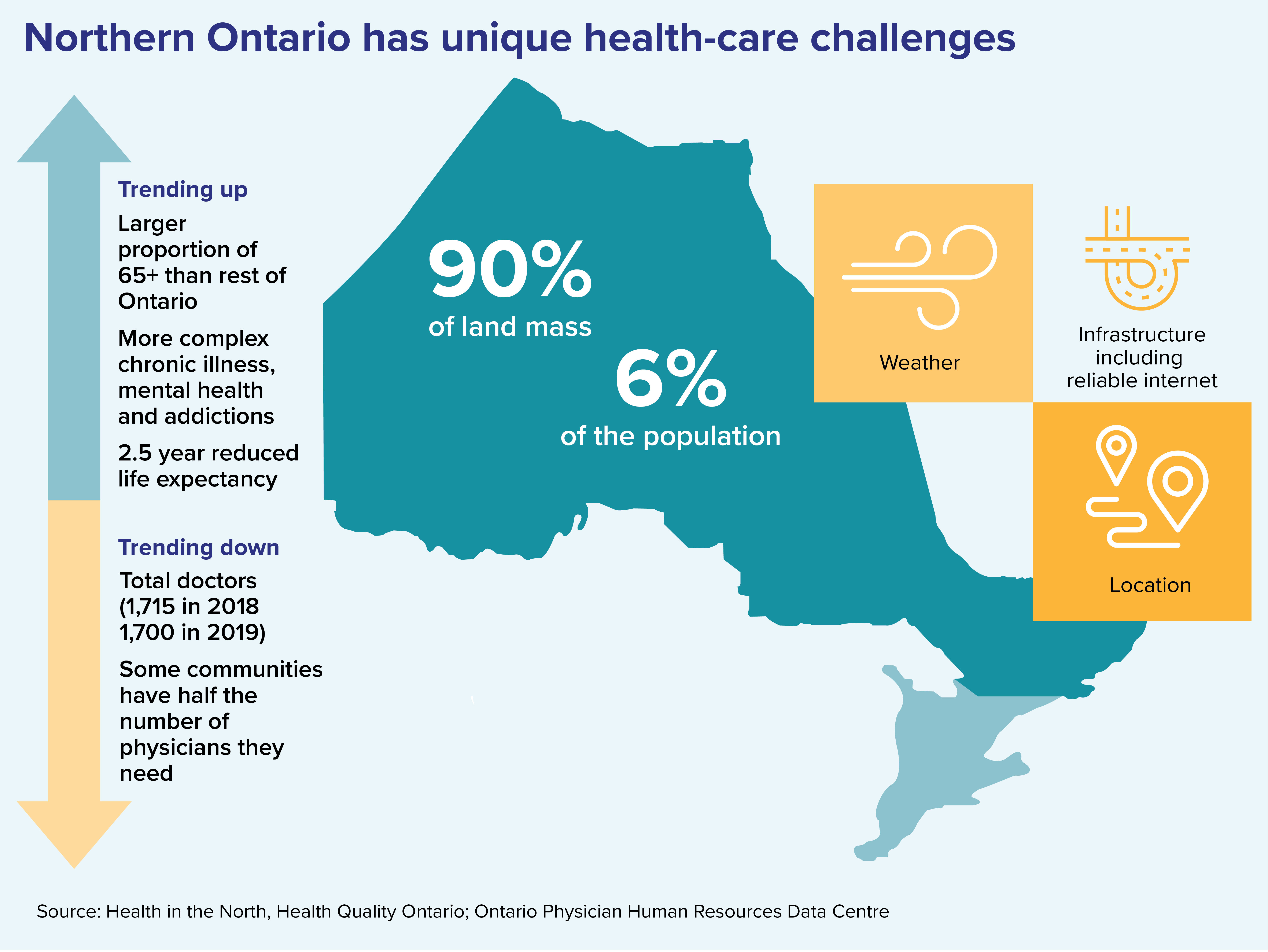

There is a shortage of doctors and health-care professionals in northern Ontario, and physical access to care and services is often hampered by weather, transportation and sheer distance. But it's crucial to the health and vibrancy of these communities.

Northern Ontario makes up almost 90 per cent of Ontario’s landmass but contains only six per cent of its population. Equitable access to health care in northern Ontario is a unique challenge, requiring unique solutions.

There is a shortage of doctors and health-care professionals in many northern communities, and physical access to care and services is often hampered by weather, transportation infrastructure and sheer distance. However, access to health care ensures healthy populations, which is crucial to the economic health and vibrancy of rural and remote communities.

Virtual care is limited by lack of high-speed internet and unreliable connectivity. It’s also hard to stay healthy when access to transportation, affordable food and secure housing are so limited. The social determinants of health must be addressed.

“Social isolation of Indigenous communities in the North, and the inequities experienced by Indigenous Peoples have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Our inequity bathtub in northern Ontario was nine-tenths full before COVID, and now it is overflowing.” – Dr. Sarita Verma, president of the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Thunder Bay

Recommendations to improve health care in northern Ontario

- That patients have equitable of access to care in their own communities

- Review and update incentives and supports for physicians and allied health-care workers to practise in northern Ontario, and other communities that are chronically underserviced

- Focus on education, training, innovation and opportunities for collaborative care to address physician (health-provider) shortages in remote communities

- Create resourced opportunities for specialist and subspecialist trainees to undertake electives and core rotations in the North

- Give medical students and residents the skills and opportunities they need to be confident in choosing rural and remote practices

- Focus on innovative culturally sensitive education and training opportunities addressing physician and other health-provider shortages in rural and remote communities

- Focus on the profound and disproportionate impact of the opioid crisis and mental health issues in northern Ontario

- More social workers, mental health and addiction care providers and resources for children’s mental health

- Enhance internet connectivity in remote areas to support virtual care, keeping in mind that virtual care will not solve health human resources problems in northern Ontario and should not replace in-person care

- A recognition of the specific need for local access to culturally safe and linguistically appropriate health care for northern Ontario’s francophone population and Indigenous Peoples

- A collaborative partnership with Indigenous Services Canada and Health Canada to address issues of safe drinking water, and adequacy of health-care facilities and resources in Indigenous communities

- Using a harm reduction, anti oppressive lens, address the education gaps in Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous communities, as health is directly affected by education

Related stories from the Ontario Medical Review

Fall 2021 issue

Physicians teetering on 'edge of a cliff'

Fall 2021 issue